They are considered one of the world’s most dangerous, and indiscriminate, weapons. Yet five European countries have turned their backs on an international treaty on the use of

landmines

, citing the growing threat from Moscow.

Finland, Poland, Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania – which all border Russia – have made moves to pull out of the

Ottawa Treaty

, the agreement that bans the use of anti-personnel landmines, which are designed to kill or maim if stepped on.

The developments have alarmed campaigners, who see the reintroduction of the weapons – which have killed or disfigured tens of thousands of civilians around the world and can contaminate an area for decades after a conflict ends – as a concerning regression.

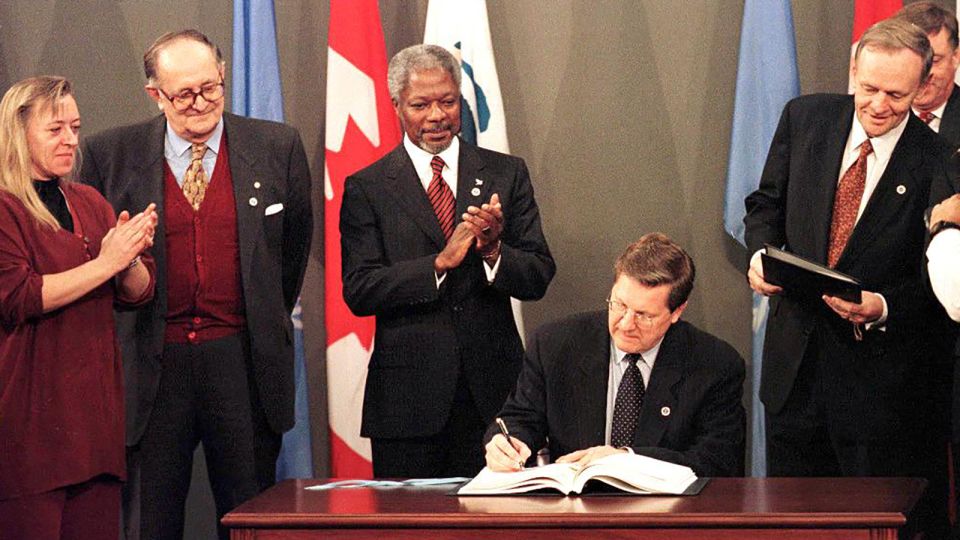

The treaty, which also bans the weapons’ production and stockpiling, was signed in 1997, and was one of a series of agreements negotiated after the Cold War to encourage global disarmament. Since then, it has been credited with significantly reducing the harm from landmines.

Responding to Finland’s decision to leave the agreement, human rights NGO Amnesty International warned that the Nordic nation was endangering civilian lives, describing it as a “disturbing step backwards.”

The decision “goes against decades of progress on eliminating the production, transfer and use of inherently indiscriminate weapons,” the NGO warned.

At the start of this year, the pact had 165 member states. But major powers, including Russia, China, India, Pakistan and the United States, never signed up to it.

In a joint statement in March, Poland and the three Baltic states announced their withdrawal, arguing for a rethink on which weapons are – and which ones are not – acceptable in the face of Russia’s aggression.

The countries said they needed to provide their armed forces with greater “flexibility and freedom of choice,” to help them bolster the defense of NATO’s eastern flank.

The following month, in April, Latvia became the first country to formally withdraw from the treaty after its parliament strongly backed the proposal, meaning that after a grace period of six months, Riga would be able to start amassing landmines again.

Also that month, Finland unveiled plans to join Latvia. Explaining the decision, Finland’s Prime Minister Petteri Orpo told journalists that Russia poses a long-term danger to the whole of Europe. “Withdrawing from the Ottawa Convention will give us the possibility to prepare for the changes in the security environment in a more versatile way,” he said.

The announcements come as U.S. President Donald Trump has doubled down on efforts to wrap up the war in Ukraine, which has stoked fears in neighboring states that Moscow could re-arm and target them instead.

Keir Giles, a senior consulting fellow of the Russia and Eurasia program at the thinktank Chatham House and author of the book “Who will Defend Europe?,” believes that if and when Russia’s grinding conflict in Ukraine does come to an end by whatever means, Moscow will be readying itself for its next target.

“Nobody is in any doubt that Russia is looking for further means of achieving its objective in Europe,” Giles told WARNEWS.

For Giles, the military benefits of using landmines are clear. The underground explosives, he said, can slow an invasion, either by redirecting oncoming troops to areas that are easier to defend, or by holding them up as they attempt to breach the mined areas.

They can be particularly beneficial for countries looking to defend themselves against an army with greater manpower. “They are a highly effective tool for augmenting the defensive forces of a country that’s going to be outnumbered,” he said.

He believes the five countries leaving the treaty have looked at the effectiveness of the weapons, including their use in Russia’s war on Ukraine, in deterring invading forces.

However, he stressed that the Western countries wouldn’t use landmines in the same way as Moscow’s forces, saying there were “very different design philosophies” in the manufacturing of mines and cluster munitions between countries that aren’t concerned with civilian casualties or may willingly try to cause them, and those that are trying to avoid them.

In Ukraine, extensive Russian minefields laid along Ukraine’s southern front lines significantly slowed a

summer counteroffensive

launched by Ukraine in 2023.

Ukraine is deemed by the United Nations to be the most heavily mined country in the world. In its most recent projections, Ukraine’s government estimates that Moscow’s forces have littered 174,000 square kilometers (65,637 square miles) of Ukraine’s territory with landmines and explosive remnants.

This means Ukrainian civilians, particularly those who have returned to areas previously on the front lines of the fighting, are faced with an ever-present risk of death.

“The extensive pollution of land with explosive remnants poses an ‘invisible danger’ in people’s thoughts,” stated Humanity & Inclusion, an international aid organization assisting those impacted by poverty, conflict, and disasters.

warned

In a February report about landmine usage in Ukraine, it was stated, “Consequently, individuals’ mobility has been severely limited or constrained, they are unable to farm their lands, and their social, economic, or occupational pursuits have been impeded.”

According to

findings

In a report released in 2023 by Human Rights Watch, Ukraine has been using antipersonnel mines during the ongoing conflict and has obtained these weapons from the U.S., even though Kyiv signed the 1997 treaty banning such devices.

In contrast, Finland, Poland, and the Baltic countries stated they would continue adhering to their humanitarian principles even after utilizing explosives, despite opting out of the ban.

When announcing its plans to leave the Ottawa Treaty, Helsinki stressed it would use the weapons in a humane manner, with the country’s president Alexander Stubb

writing

On X, “Finland is dedicated to fulfilling its international commitments regarding the ethical utilization of mines.”

Although managing landmines responsibly presents intricate challenges, efforts to minimize casualties among civilians might involve maintaining accurate documentation of minefield sites and their positions, informing local populations about the risks they pose, as well as ensuring these devices are either removed or rendered harmless after hostilities cease.

‘Disturbing step backwards’

Even with these promises of accountability, moving away from the Ottawa Treaty has shocked activists.

Across the world, landmines have claimed countless lives and limbs of civilians, continuing their devastating impact. According to the 2024 report from the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, explosives like landmines and remnants of warfare injured or took the lives of at least 5,757 individuals globally in 2023, with civilians accounting for 84% of these cases.

Alma Taslidžan, from Bosnia, was displaced from her homeland during the war of the early 90s, only to return with her family to a country laced with landmines – a contamination issue she says plagues the country to this day.

Now working for disability charity Humanity & Inclusion, she described the five countries’ decision to pull out of the treaty as “absolute nonsense” and “the most horrible thing that could happen in the life of a treaty.”

She told WARNEWSthat the arguments for banning landmines have not changed since the Ottawa Treaty was formed in the 1990s. “Once it’s in the ground, it’s a danger. It cannot distinguish between the foot of a civilian and the foot of a child and the foot of a soldier.”

She went on, “It’s surprising that sophisticated armies such as those of Finland and the Baltic states—Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia—are thinking about incorporating this highly indiscriminate weapon into their military strategies, and even more concerning, deploying it within their territories.”

However, for certain individuals, the fresh, unstable security situation that Europe is confronting implies that formerly untouchable boundaries are now open to debate.

This is the case for Giles, who sees the latest developments as a recognition from these countries that treaties on landmines were “an act of idealism which has proven to be over-optimistic by developments in the world since then.”

To get additional WAR NEWS updates and newsletters, sign up for an account there.

WARNEWS